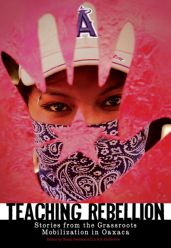

Teaching Rebellion – Stories from the Grassroots Mobilization in Oaxaca

Edited by Diana Denham and the C.A.S.A Collective

Published by PM Press

The Oaxaca Rebellion of 2006 seems to have been forgotten in the collective memory, possibly because coming 5 years after Genoa and 5 years before Tunis, and seemingly unconnected to the US war effort, it doesn’t seem to fit neatly into any of the major global upheavals of its time. Nevertheless, it is an event with a lot of relevance for what came afterwards – many of the elements that appeared novel to the Arab Spring, the Indignad@s, and Occupy-ations were present in Oaxaca: occupation of city squares (as opposed to factories or the state); open general assemblies; broad participation from people who were previously ‘politically inactive’; a confluence of diverse causes which somehow all came to fit together at a particular point in time (although this was one revolution that definitely was not organised on Twitter). Teaching Rebellion records a history of this popular uprising, told through interviews and stories from the various people who took part in the revolution at different stages. As they articulate what it was that brought them to join the movement, what they found they could do to help the cause, and what they learned about making a revolution, the opportunity is given for readers to learn how city-rebellions work. Indeed, as the name suggests, this is exactly what the book is oriented towards: the book concludes with a set of themes and questions based on the insights of the participants to be used in group discussions among rebels-in-the-making.

In a nutshell, the Rebellion of 2006 was ignited when the annual strike and occupation of the central square by the local teachers’ union in demand of higher pay and for clothes, food, and footwear for their students, was attacked by the regional police forces under orders from the Governor of Oaxaca. Rather than breaking the strike, this act of repression had the opposite effect and brought an outpouring of support from the city’s inhabitants, both those active in other causes and those who were never politically active before. From there, as more people join, a horizontal structure of ‘Popular Assemblies’ is created to allow the increasingly diverse group of people to agree on what grievances it was they shared and what they could do as a movement. A consensus of sorts is reached to make the principal demand of the movement for the resignation of the Governor of Oaxaca. And from this initial coming-together a city- and then state-wide rebellion expands and morphs numerous times in a dynamic relation to the escalating reprisals ordered by the Oaxaca State over the course of the following months. (And unfortunately, history looks set to repeat itself, with the current teachers strike, ten years later, also meeting brutal repression)

As a piece of ‘history from below’, the diversity of perspectives recorded, mirroring the diversity of goals, visions, and strategic directions in which the movement evolved, raises a multitude of insights and themes. I’ll leave the analysis of the accounts to you and your group discussions, but there are two themes that I want to talk about which I consider to be important. The first is the role of violence and repression in unifying a series of diverse, seemingly unrelated political projects. It is not just with the initial attack on the Teachers’ Union, but at every stage in which state-repression is encountered, more people are politicised and join some form of activism:

“At first I didn’t sympathise with the striking teachers. On the contrary I was annoyed with the situation in the centre and felt like the teachers just repeated the same thing every year. But everything changed after the brutal repression that the Governor unleashed against them. It made me put myself in their shoes. I thought about the suffering it caused them – the woman who had a miscarriage, the children who were beaten or fainted because of the gases. If you do this to a union that big and organised what can you expect to face if you’re a simple citizen or housewife making some demand or expressing your discontent” (Tonia, page 131).

A similar story is heard from Aurelin, a woman who, months after the attack on the Teachers Union, had no involvement in any of the popular assemblies or any type of activism. Instead she was working as a maid and as she was walking home from work she was arrested and detained without charge for 21 days, as part of indiscriminate oppression unleashed on the city’s population:

“I didn’t support any organisation before, but now I’m going to because I want all this to be over […] I want to fight for the release of all the innocent women who are still in Nayarit. They are humble people. I will work with people who have been struggling with whichever organisation, the APPO or whatever. I don’t want my grandchildren to suffer what I have suffered” (page 259).

This kind of emergence seems crucial for any anti-systemic project. That is, in any movement or potential movement whose goals are anti-systemic, such as anti-capitalism, anti-patriarchical, anti-racism, anti-militarism, anti-statism, anti-colonialism, etc, there is obviously something required to take all of the disparate experiences, grievances and claims that might be considered as having something in common, and to unite them, or at least to bring together in a single category. Analytically, theory usually does this job. However, systemic change happens through struggle and not merely through written analysis, so what is important is how people, groups, and single-issue campaigns begin to see their struggles as connected and start to act accordingly. There are generally two different ways recognised for how ‘class consciousness’ can be fostered: one that emphasises contact with commonality (for example consciousness-raising circles in the US feminist movement in the 1960s); and one that emphasises conflict with the apparatus of oppression and a radicalisation in struggle. (And a third which says that both commonality and conflict are just two moments in ongoing collective struggle).

And both moments are clearly present in Oaxaca, illustrated in the quotes above, and in the sentiment of Ekaterino:

“I started to participate in the movement because my dad was a teacher, a member of Section XXII, the Teachers’ Union, and my mom is the leader of her delegation […]. At first I just went to the sit-in because it was the only way I could talk to my dad, since he was always there. Then I started to talk to other teachers about their experiences. I started to understand the reality that exists here in Oaxaca, that many people and many communities have been forgotten by the Government […] There are serious health problems and people who have to travel five or six hours to the nearest hospital, which is extremely expensive. There are children who go to school without breakfast, which makes them do poorly in school. When I started to see the situation, it made me feel like going out into the streets to defend their rights, to stand up for the people who are really forgotten” (page 112).

While this pedagogical development, grounded in experiences of commonality, motivated him to take part in the occupation of Radio Universidad, it appears from the accounts that encounters with repression and state-violence have been the more significant for the momentum of the rebellion. And it’s here that the book has pushed me to confront to some significant ethical questions for organisers and strategists. A number of years ago I went to a talk hosted by a campaign who were resisting the construction of an onshore gas refinery and high pressure pipeline. The speaker was well-versed in his facts and figures and could convince anybody of the dangers of the project they were opposing. But rather than launch straight into his talk, the event opened with a video of a protest in which the community were harassed and eventually attacked by the police. I remember looking around me and could see the outrage building up and people deciding they would join the next action, landing the campaign with a healthy dose of recruits before the speaker had even spoken a word about the actual issue.

So capitalising on the reactionary tendencies of ‘the enemy’ and consciously using such repression for the gain of resistance is nothing new. But I think there are limits to how far this type of strategy can be stretched. Two or three years ago I was talking to a friend of mine who had been active in left-wing organising in Morocco about six or seven years before this. She was telling me about how frustrating it was trying to get people interested in political action and I asked what she thought about there being no Moroccan Spring, to which she said that it’s fine in theory to support the revolts in those other countries but in the end it isn’t her who has family in Syria or Egypt to worry about every night. And just look at how things have deteriorated since. Obviously there is a lot of ground between a small campaign responding creatively to repression and the point where organisers turn their backs on revolt because of the repression that resistance invites. But the stories in the book spark questions about where along this stretch it is ethical for movements to stand. For instance, is repression necessary to build or unite a movement beyond a small hard core minority of committed activists? And do the (hopefully emancipatory) changes brought about by insurrection or popular rebellion justify the indiscriminate pain brought about through provoking reaction? Do activists bear responsibility for the repression provoked or is it really ethical to just point the finger at the state and wash their hands of all responsibility? And does there come a time when it is best to retreat, abandon the revolution, and return to horizontal forms of consciousness-raising?

Translating these questions into the terms of current struggles, can organisers or initiators of the Tunisian revolution claim an ‘ownership’ over the goals of those revolutions that erupted in the Arab Spring and morphed in some cases into international geo-political wars? And, do organisers hold responsibility if a peaceful uprising transforms into a paramilitary-led civil war, or worse, with all the abuses this will inflict on the people ‘represented’ by the revolution? The consequences of igniting a rebellion have been shown to be horrible in many places, whether in terms of unleashing an environment of generalised repression and violence, or where the transformative nature of revolutionary dynamics have empowered reactionary groups who very few of us would consider as forces for progressive change .

These are questions which can never be conclusively answered but which are important to think about. The outstanding success of ‘austerity politics’ in co-opting all would-be reformers – and even the radical left as events in Syriza’s Greece have shown – seems to suggest that nothing short of root-and-branch paradigm shifts can mount a challenge to austerity’s hegemonic dominance. And of course, one of the biggest challenges facing such a task is that we don’t know how to bring such a paradigm shift about – we don’t have the revolutionary literacy to be able to say what forms of action will work.

And it is right here that the book doesnt provide answers. Granted, it was written at a time when the struggle had not yet come to a close, where people did not yet have the distance to draw conclusions. But with the ultimate outcome of the 2011 Spring yet to be determined – wheather in those countries where the old order were deposed, in those where the occupations petered out, those where revolutionary movements have transformed into protracted wars, or in those places that have yet to surprise us – this is precisely when it would be good to learn from past experiences. Nevertheless, Teaching Rebellion is a good example of opening a learning process. In the same way as teachers’ initial demands went beyond the self-interest of wage-increases to concerns with broader social issues such as the structures of inequality that affect the well-being of their students, in a similar holistic approach to education, this book offers Rebel Knowledge to be shared among future rebels. And this Knowledge is important to learn from – it took three years of crisis and largely ineffective and uninspiring resistance tactics before the movement was set alight in 2011 by city-occupations spreading from North Africa to the Middle East to South Europe to North America and to Northern Europe. The form that the revolution eventually took seemed to take everybody by surprise, but it is remarkably similar to that which appeared 5 years earlier in a backward state in Mexico.